Before I worked in venture capital, I worked at a firm called Boston Consulting Group. It’s full of great talent (in particular, high-slope young professionals), interesting work, and luxurious perks. Yet top consulting firms still experience really high rates of churn. I’ve spent a good part of the past few years thinking about why that is. More specifically, how to avoid the pitfalls that lead to high churn.

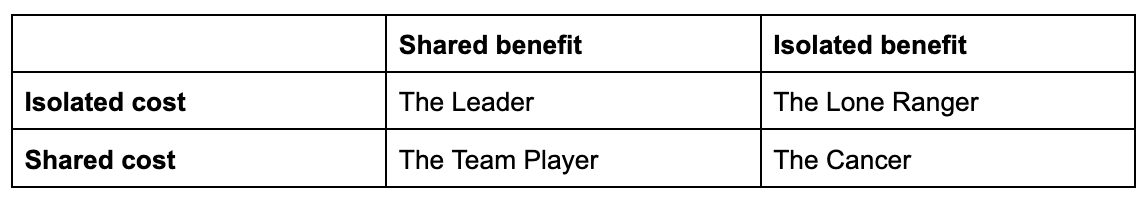

One simple framework is to view the costs and benefits undertaken / enjoyed within an organization as whether they’re shared or isolated among team members. The matrix would be as follows:

What you want to strive toward are the shared benefit quadrants, because it’s what helps the organization move forward more efficiently and most consistently.

Isolated Costs

Some degree of isolated costs but shared benefits are inevitable. Ideally, the isolated costs are distributed evenly – everyone assumes different isolated costs that produce a stronger overall team, and those shared benefits are made evident such that each person’s isolated cost feels justified.

Understandably, scenarios in which individuals experience outsized isolated costs are also inevitable. The solution I saw at BCG was to reward those individuals with extra compensation, in the form of isolated benefits: bonuses. It was a way to maintain a baseline expectation of isolated costs while rewarding individuals that embraced extra work.

The baseline level of expected isolated costs increased as individuals moved up within the organization, but so too did their base salaries. It’s ok if there’s discrepancies in baseline expectations between individuals at different positions in the hierarchy, but individuals within the same tier should have similar baseline compensation. Anything less is likely to create discontent among team members.

Isolated Benefits

Importantly, isolated benefits are not limited exclusively to financial compensation. Some clear alternatives include exposure to great learning opportunities and meaningful mentorship. The learning opportunities in particular are powerful early in one’s career, when the net present value of those learnings (and the slope on which it helps set that individual) could easily exceed a short-term cash bonus. I’m writing about these benefits from the stage of life that I’m currently in (my twenties), but I imagine that isolated benefits for people with, say, children might involve something like having more flexibility in their schedule. The key is ensuring that the isolated benefit does not become a shared cost.

The best thing the individual in charge can do is figure out what benefits matter most to their employees. This is hard and it takes effort. Actively soliciting frequent and honest feedback is one way to do this, but sometimes junior folks may be hesitant to voice their true opinions. Or quite frankly, they may just not know how. But, once a leader does figure this out, it enables them to better align incentives. And sometimes, it may even reveal that an individual’s goals are misaligned with the direction of the organization.

In theory, this works smoothly. In practice, my guess is that many people have strong preferences for short-term financial compensation. The goal should be to find talent that appreciates both tangible and intangible benefits. And even then, in the absence of these less tangible benefits, it’s likely that one’s focus turns to monetary incentives.

Churn Point #1

The point at which an individual feels their isolated costs are beyond other team members’ efforts – and that they’re not being compensated sufficiently for those extra costs – tends to be the point at which they start to think about leaving. I saw this happen fairly frequently at BCG, at all levels.

There was also somewhat of a compounding negative effect. As the best people on the team earned more trust from their managers, they were given either more work or consistently the most challenging work (or both). The extra workloads (without corresponding compensation) would create frustration, which eventually led to attrition. That, in turn, caused the remaining workload to be shifted to the remaining most capable folks on the team. And so the cycle repeated.

Shared Costs

Shared costs with shared benefits build team culture. Costs are inevitable for growth; finding ways to share them helps build camaraderie and makes everyone feel like they’re rowing in the same direction. Some of the most powerful bonding moments I experienced were at midnight in the office working on a deck with my teammates. Would I wake up tired the next day? A little, but most people wake up tired anyway. And now, years later, what I remember far more than the tiredness is the moments that built friendships and trust.

Working on a deck (read: project) together was in some ways taking a series of isolated costs and rearranging them into a shared cost. As a side note, this is one reason it’s really important to work in person: it takes the isolated costs and makes them feel shared – or, at the very least, makes it visible that everyone has undertaken their own isolated costs in service of shared benefits.

Those moments of shared cost also teach you so much about your teammates. I have so many great anecdotes; I’ll share one that has especially stuck with me:

It was the night before a big client presentation, and we were supposed to send them the deck ahead of time. The clock was closing in on 1am, and there were just three people left in the office: my project leader Sam, my colleague (and friend) Jake, and myself.

In one of the final proofreads of the deck, Jake saw Sam had changed a word in one of his slides’ titles. I can’t remember anymore what the word was (maybe a superlative), but Jake became adamant that the original title should be reinstated. They started debating. 5 minutes in, I couldn’t believe they were still arguing over it. It was 1am! How much could a word matter? Sam was the senior on the team; it’d be so easy for Jake to just capitulate and we could go home. But he didn’t, and after about 10 minutes they came to a compromise (some new, third word to use in the title). I honestly don’t remember if it ended up mattering.

What I observed in those 10 minutes was that Jake a) really cared about his work, b) paid extreme attention to detail regardless of how tired he was, and c) was willing to put in the extra effort to make sure we did what he believed was right. And what I remember most potently from that experience isn’t the 10 minutes of extra sleep I could have gotten but, rather, how much respect I gained for Jake. I’m even smiling now as I write this. If I ever start a business and need to build out a team, Jake would be one of my first calls.

Other good examples of how shared costs create camaraderie are evident in sports teams. A superstar quarterback or point guard can’t win a championship on their own. They may enjoy some isolated benefits (e.g. sponsorships) as a byproduct of their individual capabilities, but the greats are tallied by their teams’ wins. For more on this topic, I highly recommend the book The Score Takes Care of Itself about Bill Walsh, the legendary coach of the SF 49ers.

Churn Point #2

If you see an individual that is consistently utilizing shared costs for isolated benefit – especially if they are not bearing any isolated costs – they are probably a cancer in the organization. Ideally, you catch the cancer at stage 1 and not stage 3 or 4. Sometimes there’s treatment, sometimes the only option is full removal.

The consequence of letting these individuals remain is that it frustrates everyone else. That’s bad. Directly, it can lead to churn among Team Players or Team Leaders. More indirectly, it can de-motivate people from doing their work to the best of their abilities. One way to create parity among effort undertaken is to add benefits to those enduring outsized costs. But another is for those individuals to simply try and reduce their own costs – putting the cost/benefit ratio more on par with how they perceive others are balancing the two. Again, my hypothesis is that top talent will eventually seek greener pastures rather than trying to taper their overall efforts. Self-limiting their efforts often just goes against the grain of how they operate.

Shared Benefits

Shared benefits seem like the ultimate goal worth striving for. So the question becomes: how do you incentivize pursuit of shared benefits?

For one, the perceived upside from shared benefits needs to outweigh what would happen if all benefits were isolated. It’s a “whole is bigger than the sum of the parts” type of mentality. Frequent communication / reminders about the organization’s mission are one way to continuously orient team members around the shared output. That, of course, requires having a mission worth striving for.

Another mechanism is to facilitate activities in which team members spend time together. This, of course, requires that team members like each other. (If they don’t, the organization probably has bigger issues). Enjoying each others’ company is a clear opportunity for shared benefit unique to the organization.

There are certainly others that I’m blanking on here. Ultimately, though, shared benefits are primarily outputs. Inputs are what’s most directly controllable.

Churn Point #3

The remaining churn points tend to come from permutations of the matrix. Until now, I’ve described it mainly as 1-dimensional: the same individual is involved in both the costs and the benefits.

But consider a scenario in which an individual undertakes an isolated cost in service of someone else’s isolated benefit. Bad managers do this: they may assign a junior with a cost-type task that creates benefit for the manager (and manager only). Importantly, it may not be intentional or malicious. One way to spot when this is happening is if it feels like a manager has to overly communicate a manufactured-feeling message about the shared value the task creates. In those scenarios, the junior person should ask if there is another way to achieve the shared benefit that does not involve such a direct, isolated cost. If the answer is yes, it’s a sign that they are undertaking an isolated cost for someone else’s isolated benefit.

While leaders should strive to avoid such scenarios, it’s possible that they’re occasionally inevitable. But if they become frequent, it will almost certainly lead to churn among those bearing the costs.

I haven’t thought through all the other possible permutations, but I’m sure there are many more. I’ll leave that as an exercise for the reader.

Final Thoughts

Some other considerations worth noting, even though they didn’t fit cleanly into the flow above:

-

Isolated costs can be really hard to unearth. They’re often born in private. They can be especially hidden to other team members when an organization is remote. Just because something isn’t visible doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist.

-

Some churn is inevitable. Not all churn is the same. The goal should be for those who do churn to feel some persisting sense of gratitude for their colleagues and time they spent at the organization. At BCG, we called this the “diaspora” model. It was well-known that churn was inevitable. So the hope was that as ex-BCG employees pursued new opportunities, they would eventually send business back to BCG. That diaspora of former BCG employees drove a lot of company growth.

-

Isolated benefits are also inevitable. Isolated benefits can be a byproduct of hard work. People learn at different rates, so the pace of individual growth is inherently likely to differ. As such, so long as those benefits are being enjoyed in excess of the shared benefits the individual helps contribute, those scenarios should not be viewed as problematic. In fact, they should probably even be encouraged. The latter is especially true if those individuals' learnings eventually translate into shared benefits for the team – in the form of strengthened knowledge, perspective, or performance the individual is able to contribute to shared causes. That’s how an organization really compounds.

I’ve written this from the perspective of how to retain talent. An organization is really just a network of individuals working toward a series of shared goals. By that logic, the framework can easily be extended to designing incentives in other types of networks with diverse stakeholders. But this piece is already pretty long, so I’ll cap it here.