It’s unlikely that many have heard of Bowie Bonds.

I hadn’t until my junior year of college, neck-deep in finance courses. At the time, I was taking a course on capital markets and one of the lectures focused on different forms of securitization. Most of the lecture was about the 2008 financial crisis — collateralized debt obligations, mortgage-backed securities, and the whatnot. But for five minutes at the end, my professor brought up Bowie Bonds.

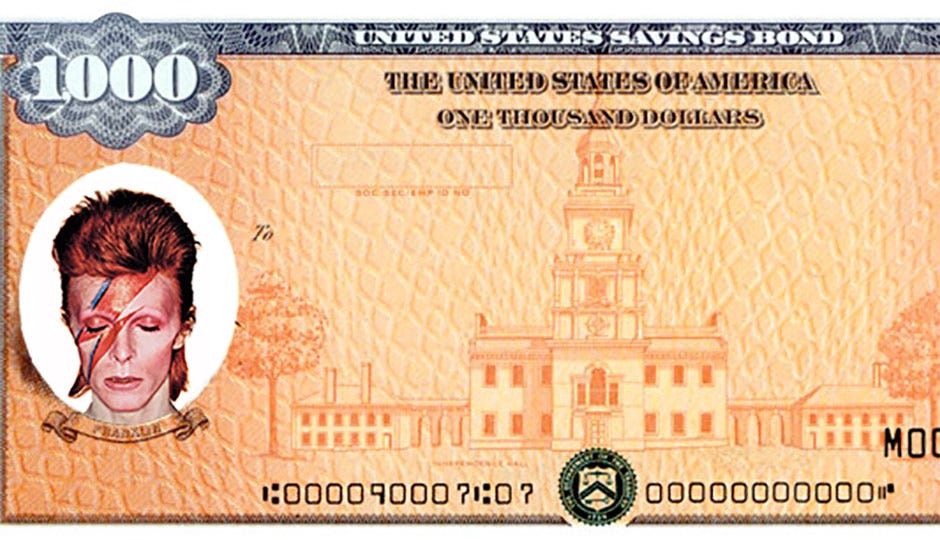

In 1997, David Bowie wanted a liquidity event. Instead of steadily receiving royalties from his 25-album music catalog throughout the next decade, Bowie decided he’d rather receive a lump-sum payment. This led to Bowie Bonds: a set of bonds backed by the royalties from Bowie’s music catalog. Notably, Bowie wasn’t selling his music indefinitely. The bonds had a maturity of 10 years so, in 2007, Bowie regained the rights to the catalog’s income stream.

In many ways, Bowie Bonds seem like an early version of creator tokens. They took an artist’s revenue stream (in the case of Bowie, future royalties from his albums) and securitized it such that those cash streams could be bought, sold, and bet on. Note that I said “early” — there are key differences between Bowie Bonds and the financial constructions we’re beginning to see in web3 today.

But we can still learn a lot from Bowie Bonds. They provide a framework for thinking about some of the biggest questions facing creator token design today, as well as how these tokens may be regulated.

When constructing a creator token, I think the first big question is determining what assets back a creator token. I imagine it’s actually somewhat of a tricky process, so let me illustrate it with an example:

Say I was watching Emma Chamberlain in 2017, loved her YouTube content, and wanted to support her. In this theoretical example, let’s say she had a creator token and I bought some not only because I was such a fan, but also because I believed her popularity would continue to grow and I wanted to share in the upside.

What would I actually be buying? What income streams back the asset? Would it be a portion of the income from her channel’s advertising revenue? What about all of the sponsorships she does? When she started Chamberlain Coffee in 2019 — whose success is arguably tied to her popularity on YouTube — would the company’s earnings flow into the token? What happened if she started a new channel — would those earnings also flow into the creator token?

The central question behind these questions is whether the token is tied to the creator or the creator’s work.

If it’s tied to the creator, the income from everything that they build should flow into the token. But if it’s tied to a set of work, the creator is free to start new business endeavors without feeling like they’ve already sacrificed a significant portion of their equity. That then leads to another set of considerations. If all of a creator’s existing and future streams of income are tied to the token, it can stifle creativity and make the creator feel like they sold out too early (especially if they used an initial token sale early in their career to gain access to capital). On the other hand, if the token is only tied to existing streams of income, what’s to stop, say, a YouTuber from just replicating their work on a new channel?

Bowie Bonds provide a solid framework for thinking about these concerns. At bond issuance, it was clearly outlined that the entirety of the royalty streams from Bowie’s first 25 albums would back the bonds. He was free to continue making music, and it was clear that revenue from new music would not flow into the bonds’ yield. Investors believed enough in the popularity of Bowie’s existing catalog to buy a piece of it. They were betting on what he had already created, not what they believed he would make next.

This model works well if you consider creators whose work generates passive income. YouTube channels are a great example. Every time a video is watched, regardless of if it’s from five days ago or five years ago, it generates income for the creator.

Something like a newsletter, however, is trickier. If that newsletter generates revenue by selling ads on a weekly basis, there’s no passive income (excluding referral links embedded within older articles). Consistent output is required to make money. Essentially two options arise. First, the token could be tied to the creator — in which case, if the creator gets bored of the newsletter but starts another venture, tokenholders still benefit. The second option is to create some initial agreement between the creator and the tokenholders that the creator will continue to publish at a certain cadence, for a certain amount of time.

Option #2 raises another set of questions. In particular:

How do you determine a time horizon for the assets that flow into the token?

I actually quite like the bond model employed by Bowie for assets with existing and passive income streams. The notion that you essentially lend out your assets for a finite time, with the full intention of regaining those assets, offers the ability to access capital without indefinitely forfeiting your work. In a lot of ways, it’s actually like what Pipe enables now, where creators or businesses with recurring revenue can trade those future cash flows for upfront capital. The difference between this model and Pipe, however, is that creators would be lending their existing assets, not their anticipated future works.

But what if the creator doesn’t have assets with passive income, such as in the newsletter example? If the creator feels forced to create at a certain cadence, the quality of their work might decline. Imagine what would happen if they hit writers’ block one week, but still need to publish anyway. It could negatively impact their work, which in turn would hurt the token’s value. Additionally, (and this applies to both scenarios), what happens as the token nears maturity? It would likely decline in value as the creator nears the end of their “contract” with the tokenholders, which ironically counteracts the actual goal of the token (tokenholders wouldn’t actually be able to share in the upside as the creator’s business grows).

There’s clearly no one right answer for crafting a creator token.

Mimicking Bowie Bonds seems to be the most straightforward path, but really only works under a narrow set of circumstances. Tying the token to the entirety of a creator’s existing and future streams of work seems the option most aligned with enabling supporters to share in the upside, but I think tying a token to an individual would be a bad financial deal for the creator in the long-run while (likely) significantly affecting their mental health.

Web3 is often referenced as an important part of the “ownership economy,” in large part because it enables creators to monetize in creative ways while owning both their work and a part of the platforms. But creator tokens can start to take us down a more dystopian path in the ownership economy — one where the fans start to own the creators. The (often negative) feedback loops created by likes and follows today will only be magnified when directly tied to a dollar value.

So, while I’m optimistic about most things in crypto, creator tokens make me a bit skeptical. They (seem like they) may only work in a limited set of scenarios. That’s not to say it can’t be done — Jaylen Clark, a NCAA basketball player at UCLA, launched a token called $JROCK in which holders get access to special events and exclusive merchandise.

But $JROCK is more like a ticket than a token. True creator tokens will be difficult to design, and even more difficult to successfully implement. I think we’re going to see a lot of trial and error — and that’s ok. The overall goals are admirable: enabling creators to access additional sources of capital, allowing fans to share in the upside from investing time and money into supporting their favorite creators, and deepening the relationship between those fans and creators. There’s just a lot of second-order consequences that stem from trying to align each of those goals.

Overall, it will certainly be interesting to watch how the space evolves.

Thank you to Spencer for reading drafts of this essay.